This guide is for self-reliant people who want to prepare for injuries that are more serious than daily scrapes and/or for situations where professional medical care might not be available — such as natural disasters, rural car accidents, SHTF, or getting lost and injured on an outdoor expedition.

Context matters! This is not a watered-down OSHA first aid kit you might keep in an office or classroom, for example, because an office typically isn’t preparing for the wide range of emergencies that you are. Vice versa, some of the contents typically found in a military first aid kit don’t apply to the threats you face, or the gear requires specific training.

Although a scrape that makes your five year old scream their head off in public might feel like an emergency, you’ll want a “boo boo kit” for that and not a serious trauma kit list like this one.

People who take preparedness seriously typically learn how to make a first aid kit rather than buy the cheap pre-made ones promoted on Amazon. Off-the-shelf kits are usually junky, built for different contexts like the military or backpacking, come with stuff you don’t need, and/or require you to toss out and upgrade so many of the included items that you’re better off starting from scratch.

Note: Doing this properly is not cheap. Expect to spend over $100 for a complete survival medical kit, less for an EDC first aid kit. But you can work your way through as budget allows — it’s better to buy one correct item at a time than to waste $40 on a junk kit.

We split emergency preparedness medical supplies into two buckets:

- Portable kits you can carry with you, such as a pouch in your emergency go-bags or something you carry in your daily purse or work bag

- Supplies you keep stored at home for a wider range of issues

This list is for the portable kits. It covers the range of EDC, IFAK, and Bug Out Bag medical kits because the prioritized list of contents is roughly the same for each — it just comes down to how much you can carry and thus how far down the list you can go.

More: 145 prioritized medical supplies for your home

Working through a single prioritized list has multiple benefits:

- You can stop however far down the list makes sense for your kit — if you’re building a small EDC first aid kit for your belt or purse, for example, get as far as you can within your space and weight limits.

- You can intelligently customize or change things to suit your needs — you might need certain medications or know that you’re prone to blisters, so you can customize the list without wildly guessing what to trade away.

- If you’re on a budget or starting from scratch, you’ll at least buy the most important stuff first.

See below the fold for more details and how to split this list into tiers based on your needs.

Prioritized first aid kit list:

- Tourniquet

- Pressure dressing

- Z-fold gauze, standard 4.5” x 4 yards

- Coban roll, standard 2” x 5 yards

- Trauma shears

- Acetaminophen / Tylenol

- Ibuprofen / Advil

- Diphenhydramine / Benadryl

- Loperamide / Imodium

- Band-aids (10x, various sizes)

- Chest seals (1 pair)

- Tweezers

- Irrigation syringe, 20cc with an 18 gauge tip

- White petroleum jelly / Vaseline in small container

- Silk medical tape roll, 1” wide

- Needle & thread stored in isopropyl alcohol (2x needle/thread, 1x small container)

- Moleskin, 5” x 2” strip

- Rolled gauze, standard 4.5” x 4 yards

- Gauze pads, 4” x 4” (6x)

- Plastic cling wrap, 2” wide roll

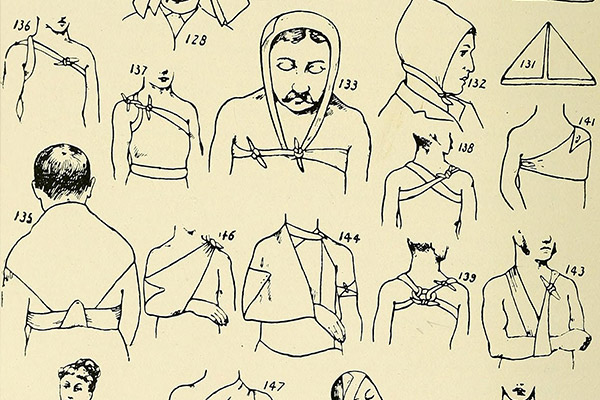

- Cravat / triangular bandage, 45” x 45” x 63”

- Butterfly bandages, 0.5″ x 2.75″ (16x)

- Safety pins (3x, various sizes)

- Elastic wrap / ACE bandage, standard 4” x 5 yards

- Aluminum splint, 36”

- Emergency blanket (2x)

- Gloves (2 pairs)

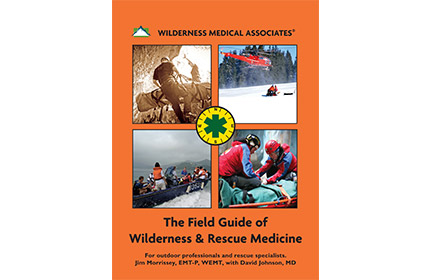

- Reference guide

- Saline eye drops

- Abdominal pad (sometimes “ab pad”), 5” x 9” (2x)

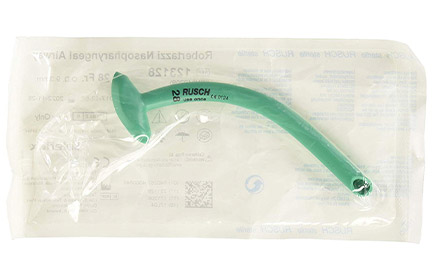

- Nasopharyngeal airway, 28 French (a unit of size used for these devices)

- Aspirin / Bayer

- Pepto-Bismol pills

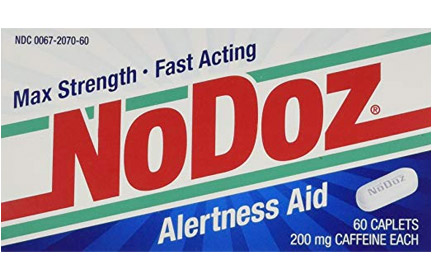

- Caffeine pills

- Hydrocortisone cream

- Miconazole

- Doxycycline and/or Bactrim antibiotics

Use your head. Get professional help if you can.

The Prepared teaches survival medicine: what to do in emergencies when you can’t depend on normal help or supplies. How to make decisions, steps to take, gear to use… there’s a huge difference in the right answers between daily life and a survival situation.

You agree not to hold us responsible if you choose to do something stupid anyway.

Want more free guides from medical and survival experts delivered straight to your inbox?

Why you can trust us

Although you should always be skeptical of medical advice on the internet, this guide was built with over 100 hours of research and debate by experts with over 180 years of combined experience working in and teaching various levels of medicine. Some of your guides:

What these first aid kits look like in real life

Although you can stop at any point down the list, we split it up into three common levels:

- Level 1: The smallest, typically used as an Everyday Carry or Individual First Aid Kit

- Level 2: A “good enough” Bug Out Bag first aid kit

- Level 3: The complete Bug Out Bag first aid kit that we recommend for serious preppers

Don’t be afraid to customize

It’s impossible to make a simple but universal checklist because of the huge range of scenarios, what terms like a personal first aid kit can mean, where and how it will be stored or carried, size, purpose, and individual medical needs and skills. Even local Good Samaritan laws can affect the decisions behind these items and where they rank.

We choose which items make it onto this list, and in what order, based on which products do the best job of helping typical people handle a mix of the most common yet most serious injuries in a survival scenario.

Sometimes you’ll see differences in meaning between labels like EDC first aid kits and IFAKs. In that example, even though both spiritually mean “a small portable kit you can carry on your body,” an Individual First Aid Kit is usually associated with the items military or police carry on their tactical gear for the most serious “someone’s about to die!” traumas, while an Everyday Carry kit is more associated with civilians carrying a mix of serious trauma and minor boo-boo convenience items in places like a purse or pocket.

While thinking through your medical preparedness, you want to be able to handle a wider range of issues than normal — from basic scrapes and pains to the most serious traumas — while still being portable.

That means accepting the trade offs necessary to build a well-rounded but portable trauma kit.

But this is your kit — you’re the one buying and carrying it — so it’s okay to customize as long as you understand the meaning behind those decisions and the sacrifices / tradeoffs.

Prescription medicines are an obvious way to customize. Follow your doctor’s advice! That includes understanding the priority of a prescription. Shampoo for dandruff is clearly not as important as a rescue inhaler, for example.

Note: If you or someone you love normally needs an EpiPen around, that would be the #1 overall most important item on this whole list.

Level 1: Core life-saving IFAK contents

Every kit should start with these items. But you might stop at Level 1, or even just part way through, if you’re building an ultra-portable Individual First Aid Kit for:

- your battle/duty belt

- something small you can grab and take with you while away from your shelter/BOB during a crisis, such as a scouting run to find food

- an EDC first aid kit you can throw in your daily-life bag, purse, car, locker, etc.

- an EDC kit you wear in an ankle holster or some other concealed body pouch

When you’re extremely limited in what you can carry, experts focus on the most severe injuries involving blood or breath — sometimes taught as ABC: Airway, Breathing, and Circulation — with a few common OTC meds thrown in if space allows.

Starter first aid kit or IFAK checklist:

- Tourniquet

- Pressure dressing

- Z-fold gauze, standard 4.5” x 4 yards

- Coban roll, standard 2” x 5 yards

- Trauma shears

- Acetaminophen / Tylenol

- Ibuprofen / Advil

- Diphenhydramine / Benadryl

- Loperamide / Imodium

- Band-aids (10x, various sizes)

- Chest seals (1 pair)

Tourniquets are included because they’re purpose-built to control the kind of sudden, massive, spurting arterial bleeding that can kill a person within minutes. That’s why professionals often keep tourniquets strapped to the outside of their gear, holding one of the most prominent “I need to get this fast” spots.

See the review of the best tourniquets and learn how to use a tourniquet.

For serious bleeding

CAT Gen 7 Tourniquet

For serious bleeding

TacMed OLAES Bandage

Pressure dressings are the all-around hemorrhage control sibling to the tourniquet. The best way to get bleeding under control is through well-aimed direct pressure. Tourniquets do that well on the limbs, but they can’t be used on the torso, head, neck, or other awkward injuries. A pressure dressing, on the other hand, can be used in almost any location, with advanced features built in to help you aim the pressure where it needs to go.

See the review of the best pressure dressings and a lesson on how to use pressure dressings.

For moderate bleeding

NAR S-Rolled Gauze

Z-fold gauze (sometimes S-rolled) is normal gauze that’s packaged in a way that makes it much easier to use in urgent life-saving situations — namely wound packing. Hemostatic z-fold gauze is even better because it has blood-stop agents built in. Clotting agents aren’t critical (you can control the bleeding without it) and add to the cost, but they can shortcut your success by a few minutes.

Coban (also known as vet wrap) is a versatile tape that sticks to itself in a way similar to plastic kitchen wrap. It’s great for small bandaging tasks and securing splints. Plus it can be reused if handled carefully and not exposed to high heat, which melts the layers together. We like these individually-wrapped 2” x 5-yard rolls are the right size.

Does the job:

Ever Ready Titanium Trauma Shears

Worthy upgrade:

Leatherman Raptor

Trauma shears are a big help when things like clothing or seatbelts are blocking your access to an injury because it’s important to get close to the skin. You may have a knife on you, but shears are clearly safer (and don’t look nearly as evil to bystanders). Shears are further down the list than some may expect for the same reason as gloves: They’re not super critical, and you often have alternatives nearby.

Acetaminophen (Tylenol), ibuprofen (Advil), diphenhydramine (Benadryl), and loperamide (Imodium). Although not critical for saving lives, these core over-the-counter meds are easy to throw in a small kit and helpful in a wide range of situations. It’s possible to find single-dose packets, like what you’d buy at a truck stop, or you can assemble your own baggies/container.

When comparing common pain relievers — namely acetaminophen, aspirin, and ibuprofen — acetaminophen (Tylenol) is the single best universal choice because it’s the safer of the three drugs. Ibuprofen can cause problems in people with clotting disorders, high blood pressure, heart disease, kidney problems, or who are elderly. Aspirin should not be given to children, and it does reduce the body’s ability to clot, much like ibuprofen. Acetaminophen is generally fine for pregnant women and is the only thing kids under six months can take for fevers.

We throw in ibuprofen at this level as well, though, because it reduces inflammation better than acetaminophen. An anti-inflammatory could be helpful for something like a sprained ankle.

There’s also evidence that when acetaminophen and ibuprofen are combined (especially with caffeine, included further down the list), the ‘ensemble effect’ creates pain relief similar to a stronger opioid. So this mix covers your daily, moderate, and potentially severe needs.

Benadryl is an antihistamine, helpful for treating allergies, hay fever, cold symptoms, and even insomnia. Everyone should carry some, regardless of whether you have an allergy that’s severe enough to justify an EpiPen. If you do need an EpiPen, keep in mind that the shot only treats the symptoms for 15-20 minutes, which buys time for the Benadryl to treat the underlying causes.

Imodium treats the effects of diarrhea. Emergencies can really screw up your digestive system through stress, difficult environments, and food your body isn’t used to (eg. freeze-dried survival food). That can easily lead to diarrhea, which, besides being an unhappy thing to deal with, leads to dehydration, fatigue, and other dangerous problems.

When we’re in a combat zone, for example, we’re often giving out Imodium to some of our soldiers on a daily basis. Even just the relatively-routine stress of going out on a patrol can cause some of the toughest people on earth to be out of commission due to diarrhea.

Tip: Buy the pill or tablet form of medications. Capsules and gels are too fragile for prepping.

Band-aids are an all-in-one dressing and bandage combo. A larger medical kit will split out those different components, but for a small EDC/IFAK kit, band-aids do well enough. Carry at least 10 in different sizes.

Band-Aid Variety Pack

HyFin Chest Seal

Chest seals help when a penetrating trauma (like a bullet or knife) affects the lung area. See the links below for details why, but if the chest is punctured, breathing can get very difficult or stop altogether. A chest seal does exactly what it says: it’s a thin sheet that you slap over a hole, like patching a leak in a boat hull. Thankfully, chest seals are pretty compact and easy to carry in an EDC kit.

You often see chest seals in the top 3-4 items of a military IFAK — which makes sense as a kit built for fighting — and we considered ranking them that highly on this list. But the likelihood of those kinds of injuries is low enough that we moved chest seals after the common medications.

See the chest seal review.

Level 2: “Good enough” go-bag first aid kit

Level 2 is the 80-20 or “good enough” first aid kit for your Bug Out Bag, Get Home Bag, or car kit. If you have everything in Level 1 and Level 2, you won’t have the type of kit that would get an “impressive!” smile and nod from a medic, but you’ll be able to handle a wide range of emergencies.

Continuing from the Level 1 list, add:

- Tweezers

- Irrigation syringe, 20cc with an 18 gauge tip

- White petroleum jelly / Vaseline in small container

- Needle & thread stored in isopropyl alcohol (2x needle/thread, 1x small container)

- Silk medical tape roll, 1” wide

- Moleskin, 5” x 2” strip

- Rolled gauze, standard 4.5” x 4 yards

- Gauze pads, 4” x 4” (6x)

- Plastic cling wrap, 2” wide roll

- Cravat / triangular bandage, 45” x 45” x 63”

- Butterfly bandages, 0.5″ x 2.75″ (16x)

- Safety pins (3x, various sizes)

- Elastic wrap / ACE bandage, standard 4” x 5 yards

- Aluminum splint, 36”

TecUnite 20cc Irrigation Syringe

Tweezers and an irrigation syringe are the two most basic items you need to properly clean wounds in the field, which greatly reduces the chances of infection and can speed up healing. The syringe is used to aim and force clean water into a wound to flush out contamination and debris. The tweezers are used to pick out whatever chunkier stuff the water can’t remove, such as a visible sliver of wood pushed into the meat.

The pressure from running tap water (or even just a pour from your water bottle) is usually enough to remove most debris. But we think it’s important not to rely on running tap water for this kit, and studies show you need water pressure to properly flush away debris. We’ve found that an 18 gauge nozzle (which comes with the product linked above) creates the best water stream.

White petroleum jelly (eg. Vaseline) is useful for everything from providing a non-stick layer between the skin and dressings to healing cracked skin or lips. Petroleum jelly also makes a great fire starter when combined with gauze or cotton balls. Pick up a small tub or tube — it’ll go a long way, just make sure you use a clean finger or tool when taking out a chunk so that you don’t contaminate the whole container.

Medical tape. Duct tape and similar versions (eg. Gorilla tape) are not great for medical use because the adhesives act differently. We personally carry two forms of medical tape — silk and paper/plastic — because silk lasts longer but paper/plastic adhere better to wet skin. But, to keep things simple, you can just pick up one roll of silk tape and do your best to get skin dry beforehand.

Blister kit: Moleskin, plus a needle and thread stored in alcohol. There’s a reason movies about the military often have an experienced soldier preaching the importance of foot care. You might have no other choice than to be on your feet for a long time in an emergency, and blisters can essentially cripple you. So it’s important to prevent blisters and properly care for them when they pop up.

Many hikers preemptively put Moleskin over “hot spots” before a blister forms. And if a blister does form, Moleskin can be cut into a donut shape around the area to prevent any more friction damage.

Tip: Never put duct tape over a blister or hotspot, which will just make it worse by tearing at skin or the edges will ball up and create new friction points.

Blisters, which are medically a type of burn, should be left intact. Popping or deroofing a blister puts you at risk for infection, and, once it’s deroofed, you’ll have to spend more time and resources treating it like any other open wound.

Instead, field medics carry a needle with six inches of thread stored in a small container of isopropyl alcohol (which can also serve alcohol’s normal medical purpose). By threading the sterile needle and thread straight through a blister, leaving the thread behind and dangling out from both ends, you keep the roof intact while giving the fluid a wick to drain through.

Rolled gauze is often referred to via the popular brand name Kerlix. Pick up a 4.5-inch wide roll that’s at least 4 yards long.

This checklist has gauze in multiple places because different packaging styles and form factors are optimized for different levels of injuries. Where z-fold gauze is great for the most dire bleeding scenarios, rolled gauze makes it easy to bandage awkward areas (like around the head). It also acts as a backup for wound packing when you’re out of z-fold gauze, can be cut down into normal 4” x 4” squares, and can be used as the hard object (when still rolled) in a home-made pressure dressing.

4” x 4” gauze pads, which medics consider to be the best all-around size, can be cut down to fit or folded over to double up the thickness. Pick up 6-8 pads in thin, independent packaging.

Learn how to dress and bandage a wound.

Plastic wrap makes a great bandage because it’s cheap and transparent, so you can watch a wound over time without constantly lifting and redoing your work (which also wastes your limited resources). Although it clings to itself, it won’t adhere to a wound or skin and can be reused if handled with care. Plastic wrap also tends to keep the right amount of moisture in a wound, and you can hold something cold (like snow) on the outside to help soothe the injury.

Buy a standard kitchen roll and cut it down into a two-inch wide roll (you’ll cut other large pieces for your home medical supplies). It’s okay to squish the round roll into a flatter shape for your kit.

H&H Combat Cravat

Cravats (also known as triangular bandages) are a simple but flexible piece of cloth that’s been in use since the Napoleonic Wars. Cravats are very versatile and can be used as tie offs for splints, slings, swathes, improvised tourniquets, head and face coverings, or even water strainers.

Butterfly bandages are a thin strip of medical tape designed to hold wounds closed. Steri-strips are a common alternative, but they don’t always stick well. That’s why some pros carry steri-strips with a separate vial of benzoin, a fluid that makes the strips stickier. Butterflies technically don’t keep as tight of a wound edge as steri-strips, but the benzoin vials can be fragile, the butterflies can be repurposed more easily than strips, and we’d rather keep things simple. Pick up a box of 0.5″ x 2.75″ butterfly bandages to carry 16 in your kit (and throw the rest in your home kit).

Safety pins are handy in a variety of situations, such as a reusable bandage closure or to make a sling for a broken arm with a cravat or t-shirt.

Elastic wrap (eg. an ACE wrap) can be used for splinting or bandaging. Keep a 4-inch wide by 5-yard long roll in your kit.

NexSkin Elastic Bandage

Recon 36" Aluminum Splint

An aluminum splint, commonly referred to as a SAM Splint, is a versatile product that can be shaped into a rigid form for stability. They work well as a custom-formed splint for the elbow, wrist, finger, ankle, or toe. You can even use the splint as a makeshift C-spine stabilizer or headrest/pillow. Here’s the best 36” long splint. You can cut it down to smaller pieces — just be careful, as the cut aluminum edge will be sharp.

Level 3: Complete survival first aid kit

Complete Level 3 if you take medical preparedness seriously and want the same kit that experts put in their own family’s emergency bags. It doesn’t have everything the pros carry in a dedicated medical bag, however, because it’s still portable enough to just fit in a standard 8”x6”x4” MOLLE pouch — an appropriate size to tuck in a backpack.

Add these last items:

- Emergency blanket (2x)

- Gloves (2 pairs)

- Reference guide

- Saline eye drops

- Abdominal pad (sometimes “ab pad”), 5” x 9” (2x)

- Nasopharyngeal airway, 28 French (a unit of size used for these devices)

- Aspirin / Bayer

- Pepto-Bismol pills

- Caffeine pills

- Hydrocortisone cream

- Miconazole

- Cephalexin or Doxycycline

Emergency blankets are common among preppers and often kept in random places around the bug out bag. But we like to store them in the medical kit because you’re more likely to use them in this context — the body’s primary method for making heat is through movement, and injured/sick people tend not to move around. These lightweight, reflective blankets can insulate a patient from the ground or air while trapping the radiant body heat inside. Pick up two blankets at least 52” x 82”.

Gloves are a cheap and compact no-brainer that more people should use in an emergency. “If it’s wet and not yours, don’t touch it.” But you may be surprised to see gloves this far down the list — gloves do more to protect the patient from you, not the other way around.

It’s very unlikely that you’ll pick up something contagious from getting another person’s fluids on your hands, even if you have an exposed cut. Mucous membranes, like around your eyes, nostrils, and mouth, are far more likely to be the point of entry for something bad. So glasses or a respirator will do more to protect you than gloves will.

However, contamination does matter when treating the more serious injuries on your patient, or if you’re touching around their mucous membranes. You wear gloves to keep the grime on your hands away from their risky spots.

We prefer nitrile material rather than latex or vinyl. Some people are allergic to latex (which might be your patient, not you), and both latex and vinyl have durability and quality issues compared to nitrile. Although gloves between 3mm and 8mm thickness are common, 5mm is the sweet spot between comfort and durability.

Tip: You can also fill gloves with water, then freeze them for a DIY ice pack.

Wilderness Medical Associates Field Guide

Reference guides are carried in the field even by the most seasoned professionals. The best choice is the Wilderness Medical Associates Field Guide because it’s well organized, has clear illustrations and info, and is specifically written for austere/wilderness situations.

Saline eye drops are included because — beyond the obvious comfort reasons — many types of emergencies involve pollutants in the air that hurt or lower your ability to survive because you can’t see. Smoke from a wildfire or pepper spray during riots are good examples.

Abdominal pads are essentially just large gauze pads, originally designed to cover the large sections skin around the torso. We include these 5-inch by 9-inch pads because, if there’s an injury that requires a lot of gauze, you can quickly run through your smaller supplies.

Rusch Nasopharyngeal Airway

Nasopharyngeal airways (“NPAs”) are a simple rubber tube that help keep the upper airway (nose and throat) clear by creating a tunnel from the nostrils to the beginning of the lower airway. This can be helpful when the patient is (or is about to be) unconscious and there’s some signal that they’re not breathing normally — snoring is a decent analogy because it’s technically a corruption of the airway while unconcious. The tube is inserted through the nostrils, which can be a little awkward, so most NPAs come with a small lube packet. NPAs can also do double duty when combined with the irrigation syringe, acting as a sort of suction tube to remove mucus or blood.

Aspirin, Pepto-Bismol pills, and caffeine. Pepto Bismol is included to primarily fill the role of an antacid, although it clearly helps with other digestive issues like nausea and diarrhea. Pepto doesn’t stop symptoms are rapidly as Imodium, but it treats the underlying causes more effectively.

Caffeine can be helpful as a general stimulant if you’re beat down but have to recover quickly to survive whatever situation you’re facing. And, if you’re someone who needs their coffee to function, sudden caffeine withdrawal can cause unpleasant symptoms in an emergency. Having a dose or four on hand can help ease you down so you’re not exploding at your FEMA shelter neighbors.

No-Doz Caffeine Pills

Aspirin is good to have on hand when you have the space for more than just acetaminophen and ibuprofen because, even though it interferes with clotting more than ibuprofen, aspirin comes in a chewable form that the body can absorb rapidly. Try to carry the low-dose chewable forms of aspirin — formerly called baby aspirin, even though you’re not supposed to give it to babies.

Hydrocortisone cream treats several skin conditions, such as general itching from insect bites, poison oak/ivy, and eczema. You can skip this if you want, but it’s easy to throw in a cheap small tube.

Miconazole (Monistat) should be included if you or someone in your close group are a woman. The stress and lack of hygiene common in serious emergencies can lead to vaginal yeast infections. Monistat can also be used for other fungal infections such as ringworm, jock itch, and athlete’s foot.

Doxycycline and/or Bactrim are both generally well-tolerated, multispectral antibiotic medications. They are usually prescribed to treat infections to the upper respiratory system, ear, skin, and urinary tract. If all you have access to are other broad-spectrum and generally well-tolerated meds like Keflex, that’s okay, but they were considered second best because they’ve developed a bit of bug resistance in recent years. If you’re American and unable to easily buy antibiotics, try having a talk with your doctor about picking some up specifically for this kit.

Skip these common items

We see a lot of these kinds of lists that include gear that just doesn’t make sense. Often times it’s due to the difference in context, and sometimes it’s due to just plain lazy or uninformed writing.

Skip:

- Decompression chest needle

- Eye shield / cup

- CPR masks

- Suture kit

- Diagnostics: blood pressure cuff, stethoscope, etc.

- Knives and scalpels

- Multivitamins

- Iodine

- Hydrogen peroxide

The most common product you see in other prepper medical lists that you should actually avoid is the “chest dart” or decompression needle. It’s often included in other lists/packages because of tacticool prepper fantasies or copy-pasting from the military.

Decomp needles are used for a specific condition called Tension Pneumothorax, which is basically a collapsed lung venting air into the chest cavity or air entering into the chest from an external hole that is trapped and can’t escape.

You may remember this scene with George Clooney, Mark Wahlberg, and Ice Cube in Three Kings:

The movie makes it look easy. It isn’t. You need training (and additional equipment instead of Dr. Clooney’s magical ears) to know when to recognize this specific problem and how to do it without causing more damage.

One recent study found that, out of the 19 patients who had been given a chest dart by people with training, only four of them actually needed it, and only two of those were given the needle correctly.

Plus the patient will need professional follow-on care, like surgery in a hospital, which won’t be possible in some emergencies.

Common decomp needles are 14 gauge, which is already pretty large. But field data shows that the needle sometimes becomes plugged up with tissue and blood, requiring multiple stabs, which makes it even riskier if you don’t have training. Some kits are moving to larger 10 gauge needles to lessen this problem. Finally, a growing number of professionals are arguing for skipping the needle altogether, in every circumstance, in favor of a “finger decompression.”

The military is taking a stronger stance about including eye shields — essentially a rigid patch to protect an injured eye — because they’ve found it’s helpful for soldiers in the field. For example, wounding patterns in battle often include bullet “spall” that bounces off metallic gear riding in front of body armor and up into the eyes. But this is another example where what works for the military is not worth it for you.

CPR masks would’ve been on the list in the past, but modern guidelines are skipping mouth-to-mouth breathing altogether, making a mask moot. There are still a few wilderness medicine situations where rescue breathing is helpful — namely “correctable” situations like lightning strikes, drowning, asthma, etc. — but you’re most likely going to be with people you know, and thus aren’t as worried about random grossness. Besides, the mask is more about psychological comfort than an actual medical need anyway. If you want some, try the $2 CPR Face Shield Mask Keychain (five-pack).

Suture kits aren’t included because the chances you really need one aren’t worth the space and weight in a portable kit. People tend to overestimate the need for forced wound closure, especially in the immediate aftermath of an injury. But the kit does include butterfly bandages that can handle almost all of the situations you’ll face — without poking more holes in a patient.

Diagnostic equipment, such as a blood pressure cuff, isn’t included because they just aren’t necessary in this type of first aid kit and thus not worth the high cost of space and weight. The best data you can get from a patient is through their words, mental status, pulse, and respiratory rates — which you can gather without equipment (except perhaps a watch).

Knives, scalpels, and other specific cutting tools can be helpful in a pinch — and you’ll likely have a field knife or multi-tool with you anyway — but you want to avoid cross-contamination or accidentally cutting your patient. Even a sterile medical scalpel isn’t worth it because it’s extremely unlikely you’ll need to cut someone in the field.

Multivitamins aren’t as helpful as you might expect. Specific vitamins like B-12 or D are worth storing in your home supplies, but they’re not worth it in a portable first aid kit because the few day’s worth of pills won’t really make a difference.

Iodine is commonly used when cleaning wounds. But studies have shown that iodine can do more harm than good after 48 hours without professional care — something we have to plan for as preppers.

Hydrogen peroxide damages both bacteria and healthy cells, and has been shown to actually slow down the healing process.

Where the experts disagree

Most disagreements come down to context. An ER surgeon, for example, has fundamentally different experiences than a ski patrol medic, which might cause them to disagree on the importance of a specific item.

After screening out those obvious differences in context, these were the biggest areas of debate:

- About a third like to carry a thermometer. It’s helpful when dealing with elderly or very young patients — their bodies don’t naturally communicate temperature well — or people at risk of pre-existing conditions. But the consensus was that it’s an optional nice-to-have.

- About half prefer ibuprofen over acetaminophen as The One analgesic (if you were to only carry one). Ibuprofen is better at reducing inflammation, which can be helpful with injuries like rolled ankles. In the end, we went with the more universally-safe choice (acetaminophen) since they both work equally well in most people.

- Additional wound cleaning gear beyond the included tweezers and syringe — a Kelly forceps, tissue forcep, toothbrush (for scrubbing), and magnifying glass — were originally on the list, but removed after some tough prioritization. Some pros, particularly those with field/combat experience, carry these tools in their gear and find the extra weight worth it because cleaning wounds is one of the most likely things you’ll do in a moderate or severe emergency. But the tweezers and syringe alone will be good enough for most situations.

- Some prefer a 60cc irrigation syringe, 3x larger than the 20cc in the list. The larger capacity requires fewer refills and does a better job when using the syringe as a suction device. The larger syringes are also more likely to come with an 18 gauge nozzle tip, which we recommend regardless of the syringe size. In the end, the 60cc size was too bulky for most kits except the largest Level 3 bags.

- Whether to include more cravats than just the one large cravat on the list. Some medics like to improvise cravats and would rather not carry as many to start with. But it’s fine if you want to add one or two smaller 36” x 36” x 51” triangular bandages.

- Whether wet wipes should be considered part of the medical kit or just general hygiene kept somewhere else. There’s clearly a benefit to cleaning your hands, tools, or the area around an injury. But you’ll likely have clean water around (or the ability to make it with a survival water filter) and can get by without a dedicated medical wipe. It’s fine if you want to add a few single-serve alcohol wipes, though.

- Soap was another hygiene question. We keep concentrated camping soap in our go-bags, but don’t consider it part of the med kit.

- One medic doesn’t carry chest seals, instead improvising them out of plastic wrap (even Ziploc bags) and medical tape when needed because of how rare those types of injuries are. Chest seals are mostly used for bullet and knife wounds to the chest — rare, but critical and part of what many people prep for, so we kept them high on the list for when you take a small kit out with you in dangerous situations.

- Coban and leukotape are two products that are either highly ranked or dropped to the bottom, and we suspect it comes down to personal preference of what people were trained to use.

- Tissue glue (eg. DermaBond) is a quick way to close up a wound. It’s more of a personal preference than a scientific must-have, but we didn’t include it because you can still close wounds in other ways.

- Adding a second tourniquet and pressure dressing. The research is clear: There are times when a second tourniquet is needed to get things under control. But it’s rare enough that we felt the extra space, weight, and cost were optional.

- Feminine hygiene products are clearly something you can stock in your go-bags, but we don’t consider them part of a first aid kit — although you can use the gauze if needed.

- Whether antibiotic ointment (eg. Neosporin) is worth it. Many field medics tend to skip it, while “white-coats” tend to like it. But the research doesn’t support carrying it.