Many people learn how to stitch (suture), staple, glue, or otherwise close a wound because they imagine an emergency situation where the only chance of survival is a MacGyver surgery hack with a fishing needle and dental floss. It’s one of those skills that just seems cool — like something a Legit Prepper should know.

Reality is a little different. Even if you’re dealing with a bad injury in a SHTF scenario, forcefully closing a wound is a last resort.

It’s also difficult and risky to do without the proper medical gear — so don’t depend on fishing hooks or your red Milton office stapler.

The simpler solution is almost always the right one, and all but the most severe wounds will eventually close on their own with proper attention. Even for those that should be closed, research shows it’s often better to leave the wound open for the first day or two.

Closing a wound is the third (optional) step in the overall process:

- Stop any bleeding (use a tourniquet if it’s serious)

- Clean the wound

- Close the wound with strips, sutures, staples, or glue (if it makes sense to)

- Protect the wound with dressings and bandages

Summary of how to close a wound:

- The vast majority of wounds should be left to heal naturally

- Serious wounds in areas with activity or tension (such as an elbow or scalp) are more likely to need closure because the wound is more likely to split open during healing

- Steri-strips and butterfly bandages are usually the best choice

- Stapling is easy, if you have the right equipment

- Stitching is difficult if you’ve never practiced, but it’s the best method for high-tension or serious wounds

- Glue works, but it’s a last resort (especially if using over-the-counter superglue) that makes it hard to see and deal with infections

Use your head. Get professional help if you can.

The Prepared teaches survival medicine: what to do in emergencies when you can’t depend on normal help or supplies. How to make decisions, steps to take, gear to use… there’s a huge difference in the right answers between daily life and a survival situation.

You agree not to hold us responsible if you choose to do something stupid anyway.

Want more free guides from medical and survival experts delivered straight to your inbox?

Why you should trust us

Your three guides have 80 years of combined experience teaching or using these skills:

What is a suture?

Suture is just the medical term for normal stitches using a needle and thread — staples, butterflies, and other closure methods are not considered a suture.

Sutures are the strongest way to hold a serious wound together, especially on parts of the body where a wound is prone to splitting back open from activity. This speeds up the healing process since there is less empty space the body needs to create new tissue for.

Stitches also help reduce scarring. Although reducing scarring may seem like a superficial cosmetic concern, it’s actually a medical priority because scar tissue inhibits movement and normal body function.

How to decide if and when to close a wound

Knowing when to close or suture a wound is just as important as how.

The right answer in the vast majority of situations is to let the wound heal on its own — including nasty injuries in an austere survival situation with no access to professional medical help.

Even trained field medics only consider forced closure in any form when the wound is in a high-movement part of the body or very serious, deep, or long.

Closing a wound prematurely increases the chance of infection and makes it harder to handle infections that do pop up. (Keep in mind that infections are the biggest threat to a wound.)

Even in austere situations where a wound is the right type for forced closure, research shows it’s usually better to wait a few hours or days after the injury before closing (called Delayed Primary Closure) so you can keep an eye on potential infection, handle any pus and drainage, re-clean the wound if needed, and so on.

There’s also the added risks of forced closure. Even if you have a sterile suture kit with all the right gear, you’re still poking holes in flesh or adding chemicals that can potentially create more problems. And it’s unlikely you can depend on a clean working environment and tools or follow-up antibiotics in a survival situation.

Closing a wound with contamination still inside is a recipe for disaster. Even if you’ve cleaned the wound properly, there’s likely still some microorganisms inside, and leaving the wound open for a day or two gives the body more time to “push out the bad stuff.”

One of the biggest factors is wound location. The purpose of sutures, staples, steri-strips, and glue is to prevent a wound from splitting open while healing. That’s more likely to happen in high-activity or high-tension areas of the body.

Common body spots for sutures and closures:

- All joints

- Forehead and scalp (although it doesn’t move as much, the skin is tight)

- Butt cheek

- Back (particularly if carrying a bag or other dynamic movements)

- Feet

For example, we once did a quick stapling on the shrapnel-cut butt cheek of a Marine in combat because they were still going to be actively engaged in fast movement, long rucks, and fighting for another 12+ hours. That meant even a great bandaging job would’ve split apart as their legs and hips moved around.

But if that Marine had rest time shortly after the wound, we wouldn’t have forced it closed at all.

How to practice

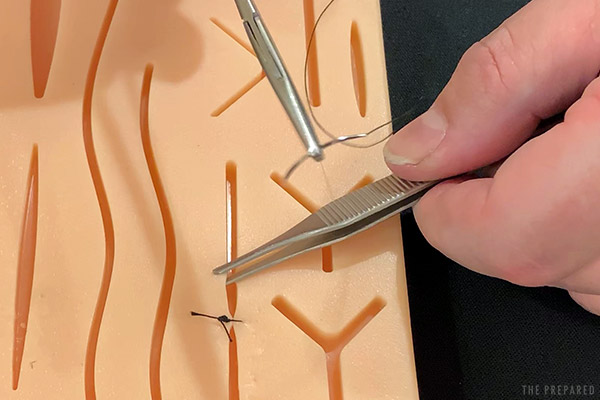

Practice Suture Kit

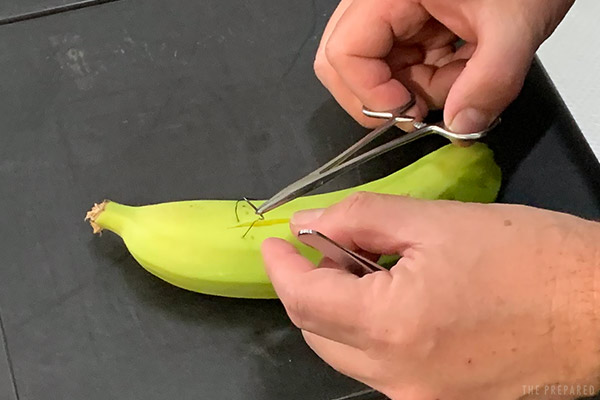

If you don’t get one of the proper practice kits, you can use a pig foot (the skin is similar to a human), chicken breast, or banana.

Approximate the edges, but avoid eversion

Wounds are rarely a clean, straight line. You’ll want to pay attention to lining up the edges before forced closure so that the wound heals cleanly and angled torquing forces don’t pull it apart.

“Approximating a wound” is the process of lining up the edges. This is usually done with your (clean or gloved) hands as you’re closing or bandaging. Be careful with your fingers when using needles.

You may encounter techniques that recommend “everting” the edge of the wound when you approximate by pushing the wound edges upward, as if you’re trying to create a skin pyramid. It was originally thought that this would reduce scar formation as wounds tend to flatten out during healing.

Current research, however, doesn’t support this dogmatic practice.

It is much more important to line the edges up and keep them flat. The research is clear about one point: make sure the edges are not inverted (tenting downward) into a canyon. Inversion will cause a larger scar that has a tendency to pucker inward.

Steri-strips, butterflies, and other simple closures are the right answer in most cases

Steri-strips and butterfly bandages are the best way to close all but the most at-risk wounds. They’re cheap, common, intuitive, easy to remove if you need to re-clean the injury, and don’t poke holes in patients.

Very complex or irregular wounds can get tricky. Just take a moment to think through the skin pattern and how many supplies you have to work with before you start your work.

Steri-strips are adhesive across the entire strip. Butterflies have a non-adhesive section in the middle.

If you think the wound is likely to become infected or you’ll need to change the closures often due weather or activity, try to use a butterfly to reduce the chance of adhesive sticking to the wound.

You can turn a steri-strip (or even tape) into a butterfly bandage using your survival knife. Cut little wings along both edges of the middle of the strip, folding them inward on the adhesive side to block the stickiness.

How to apply strip bandages:

- Approximate the edges of the wound using your (clean) fingers.

- Start in the middle of the wound. If you go outside-in you might end up with an odd bubble in the middle.

- If using a butterfly, you want to align the strip so the non-adhesive part goes over the wound when closed.

- Apply, and press down to make sure it seals to the skin.

- Alternate placing strips above and below the first strip. Stay 1/8 to 1/4 of an inch apart — too much space between them increases the tension on each one.

- Once finished, you can place more strips or tape at the ends of the bandages in parallel to the wound to anchor them down against the skin.

Tip: Another technique for helping secure strip bandages is to use tincture of benzoin. Clean the area you want to adhere with an alcohol prep pad and then apply some benzoin to the area. Place the adhesive bandage over top.

ZipStitch

ZipStitch is a newer commercial product that’s gone viral within the survival community because it looks neat and easy:

We love to see more innovation in this market and like the ZipStitch’s all-in-one package. They’ll likely hold up to more abuse than a standard strip or butterfly, too.

But at a whopping $30 each, the ZipStitch just isn’t worth it for most people. Plus the zip tie portion is rigid and doesn’t lay flat against the skin, making it more likely to get snagged or poke through bandages. And if you make a mistake, you have to throw the whole thing out (just like a normal zip tie).

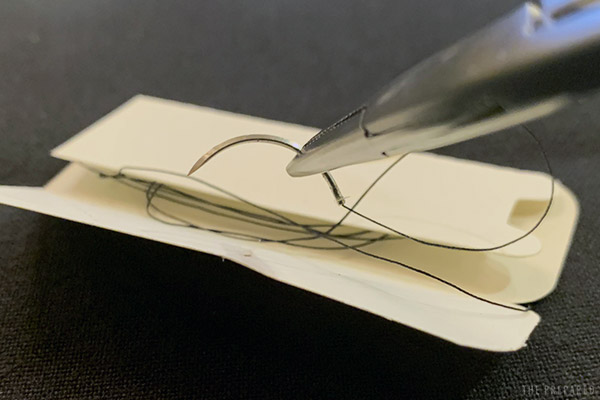

Suture kit

The basics of a good emergency suture kit:

- Suture material/thread and curved needle. This is how commercial sutures typically come.

- Forceps. You may see these referred to a “needle drivers.”

- Scissors. For cutting the thread after each throw.

- Tissue forceps. These look like tweezers with a single tooth on one side and two teeth on the other, which are used to gently grip the edge of the skin for manipulation.

- Scalpel blade. Can be used for trimming away dead tissue.

There’s a bewildering array of suture material options. Each type has strengths and weaknesses for different types of tissue.

We recommend non-absorbable nylon because it has the best strength while retaining some elasticity (which helps if the wound swells).

You should always opt for a curved needle. The most common (and most appropriate for preppers) is a “3/8 circle.”

If you have to get creative with random tools — like sewing needles, dental floss, or fishing line — do your best to make them sterile and be prepared for a more complicated task with higher risk of infection.

Tip: The smaller the first number on the suture, the stronger the thread (tensile strength). 2/0 is stronger than 6/0.

How to stitch a wound

If you’re taking a sterile needle and thread from a closed suture kit, don’t touch it with anything but your clean tool and clean/gloved hands. Unwind all of the suture from the package.

Note: The steps pictured are by a right-handed person.

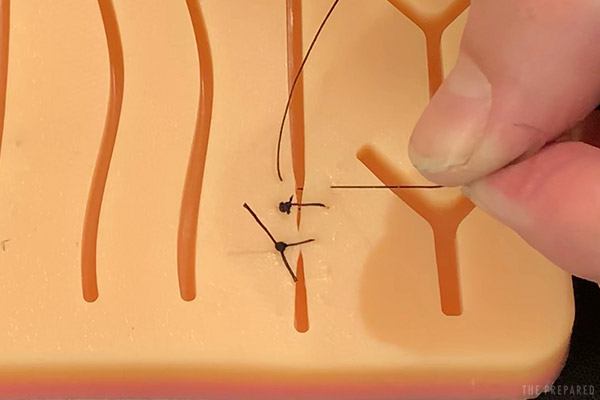

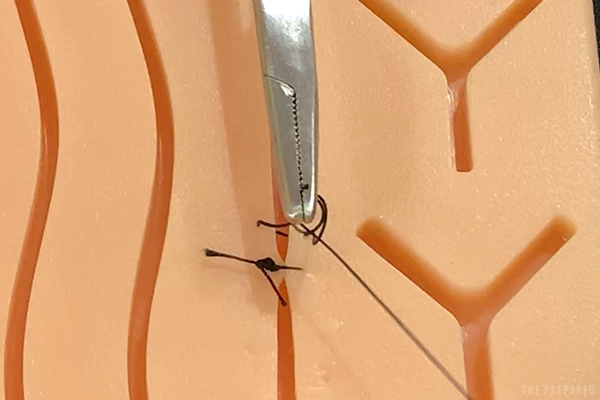

Grip the needle mid-shaft. If using a needle driver, lock the clamp.

Because we’re making one stitch at a time (rather than one long chain of stitches), it’s not a huge deal where you start stitching. Just use your head.

But it’s usually easiest to start with the edge of the wound furthest away from you (as pictured below).

Grab the edge of the wound with your tissue forceps and gently lift the edge.

Push the needle straight into the skin at a 90 degree angle about a half centimeter from the edge.

You’re just sewing the skin; don’t go deep enough to pierce fat.

Rotate your hand so that the needle starts the “U”-shaped curve, passing across the wound channel and into the other side. Don’t work with crazy angles; keep the holes on each side as square to each other as possible. You can (carefully) use your fingers to line up the wound edges.

Release the edge that you are holding with the tissue forceps and grab the opposing side. Complete the U-turn and bring the needle up through the skin on the other side.

Grab the thread just below the needle with your fingers or the needle driver. Pull the thread through until you have an inch or two left on the starting side, then place the needle down.

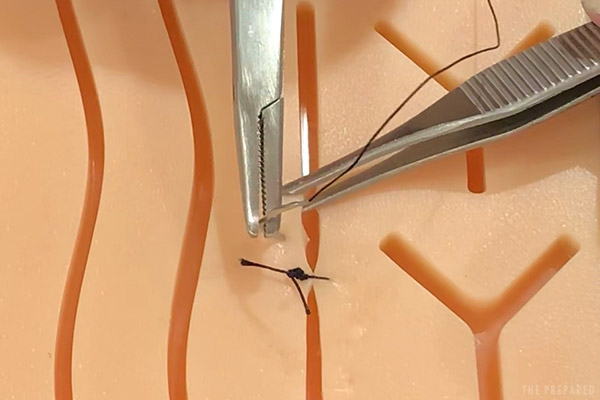

Creating the knot in the next steps might seem tricky at first. But you’re basically making a series of simple overhand knots using the needle driver tool to wrap and pinch the thread.

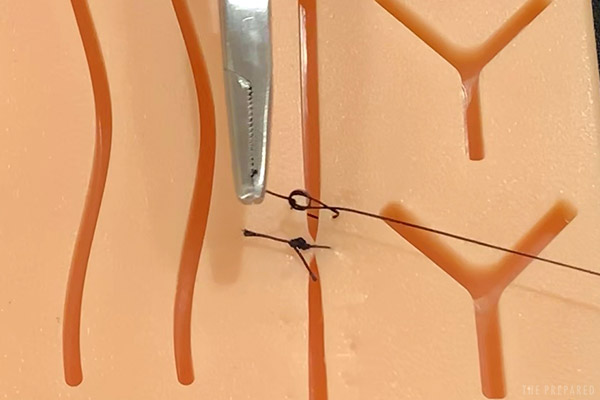

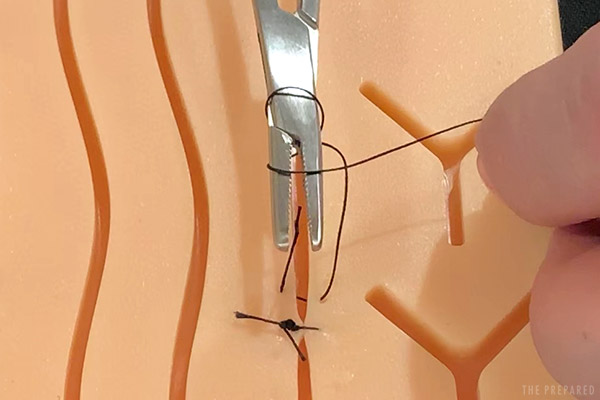

Hold the needle driver with one hand. Use your other hand to wrap the long end (the end you just pulled through) of the thread twice around the tip of the needle driver.

Pay attention to the direction (clockwise or counter-clockwise) you wrap around the forceps. It will matter later.

The wrap should be snug, but loose enough that you can still open the tip of the tool just enough to pinch some thread.

Pinch the tail/short end of the thread with needle driver clamps.

Using the hand already holding the suture thread, gently pull the thread so it slips off the tool.

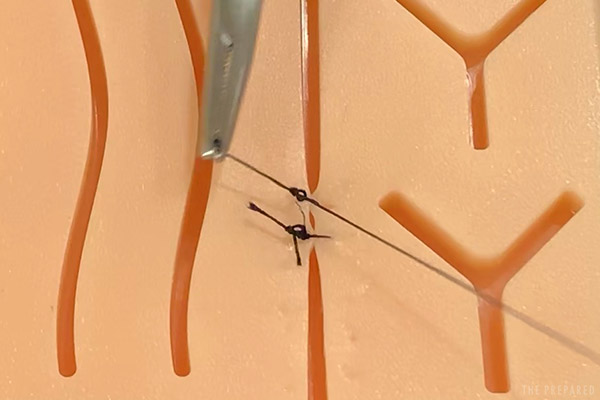

Tighten until the edges of the wound are approximated with the knot laying flat on one edge of the wound.

You just completed one “throw.” You want to end up with 5-6 throws on a given stitch, layering knots on top of each other.

Alternate the direction (clockwise or counterclockwise) of how you loop the thread around the tip of the needle driver on each throw. Switching back and forth makes the knots more secure.

Cut off the extra thread on both sides once you’re done with the throws. You don’t want to get too close to the knot, otherwise it might slip apart.

Repeat at 1/4-inch intervals until you have closed the wound.

Tip: Make removal and inspection easier by keeping all of your knots on one side of the wound.

Sutures should come out in one to two weeks. Stitches in low-use areas of the body (like the face or scalp) can come out in 7-10 days. High-use areas (like the torso or legs) should stay in for for the full 14 days.

When it is time to remove the sutures you simply cut the thread to one side of the knot and pull the thread out. Be gentle and smooth with your movement — the thread should come out easily.

Suture techniques

Suturing is a diminishable skill with multiple layers of complexity. If you don’t practice every once in a while, you’ll probably forget when the need arises years later.

There are multiple suturing techniques. For example, a professional might stitch a very deep wound in layers, starting at the deep end and working up towards the surface. Otherwise you’d just close the surface and create a hidden cave where infections throw a party like their parents are out of town.

We focus on the simplest and most relevant type of suturing: interruptive.

Unlike continuous stitching that keeps the line unbroken and only secures at the ends, interruptive stitching is done one piece at a time. Each stitch is solo.

Austere medicine experts recommend the interrupted method because, even though it’s not the simplest method to teach, it uses a small amount of suture thread for each stitch (so you can conserve resources) and is the more forgiving if you make a mistake on a particular stitch.

How to staple a wound

Stapling is much easier to do than suturing. But you run the risk of heavier scarring on the patient and it requires specific equipment.

Only use medical staplers and staples. Office staples come out in a “U” shape, then are bent by the bottom side of the stapler into the final closed form. Medical staples work differently since there isn’t a metallic backstop to force the “U” into a “B”.

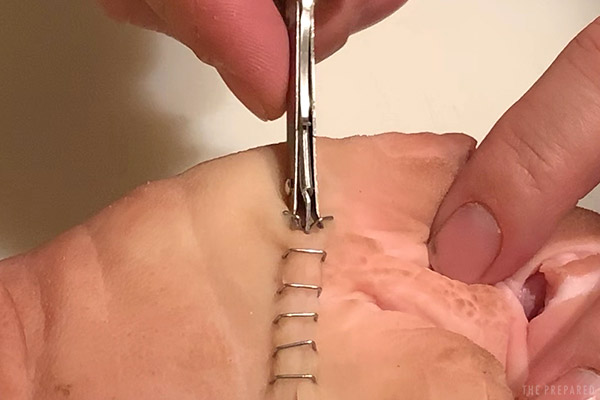

Starting at the edge of the wound, center the head of the stapler over the wound line.

Press down firmly and squeeze the stapler.

Move down 1/8 to 1/4 of an inch. Repeat.

The skin may form a natural elevated ridge under and along the staples, as seen below. It’s not a problem as long as you’re following the advice above about avoiding inversions.

Assuming there are no signs of infection in the meantime, staples should be removed from thinner, faster-healing tissues (like the scalp) in seven days. Thicker tissues (like the buttcheek) should wait for 10 days.

The best way to remove staples is with a medical staple remover. The three teeth (one on top in the middle, two on bottom) are designed to pinch the staple and fold it up and out of the wound.

Tip: If you need to improvise, try to mimic the three tooth design and motion of the medical staple remover. Don’t just grab the staples with pliers and pull — you’ll likely cause a bit of tissue damage. So take your time.

Glue

This prepper hack comes up often on social media as a cool way to easily close a wound. It does have merit, and we know overworked nurses who glue their children’s cuts before sending them back out to play. But it’s not the miracle some make it out to be.

Although it’s quick and hacky, using glue should be your last resort as a closure technique because it’s very difficult to open the wound back up if you need to treat an infection. The glue also completely shuts off the inside of the wound, potentially trapping too much moisture or contamination.

Never use glue if there are signs or high risks of infection, and avoid areas around mucous membranes (mouth, nostrils, eyes, genitals). The curing process of non-medical superglue creates chemicals that irritate mucous membranes.

The most common type of adhesive used to close a wound is cyanoacrylate, the main component of superglue. While you can technically use the little super glue tube from your toolbox, there are a few differences between civilian products and medical-grade adhesives.

Vetbond

Dermabond

Medical adhesives have different additives that make the glue less toxic and more flexible. They are less irritating to the tissues and carry a smaller risk of aggravating infections. The flexibility allows for a little bit of movement which reduces the chance of a wound tear.

Some patients can be allergic to the chemicals in the adhesive, and it should never be used in situations where wound healing can be delayed (wet environments, high altitude, very cold environments, patient is diabetic, etc.)

How to glue a wound:

- Approximate the wound edges.

- Carefully apply glue to the wound channel. Less is more, so use as little as needed.

- Hold the edges until the glue cures.

Ideally, the wound heals and the glue naturally goes away.

If you need to remove the glue, there are a couple of ways that are not pleasant. Cyanoacrylates can be removed with acetone. As you can imagine, acetone is pretty toxic to healing skin and will cause a lot of discomfort for your patient.

It’s possible the glue has seeped into the wound in such a way that tissue will need to be cut off for removal — yet another reason this is a last-resort method.