On April 15, 2021, Arizona congressional aide and Afghanistan veteran Alexander Lofgren was found dead in a remote part of the Death Valley park. His girlfriend Emily Henkel was found alive with a severe foot injury.

Some of the details about this story stood out to us as a unique learning opportunity, eg. how they left a note with their car that included their destination and resources.

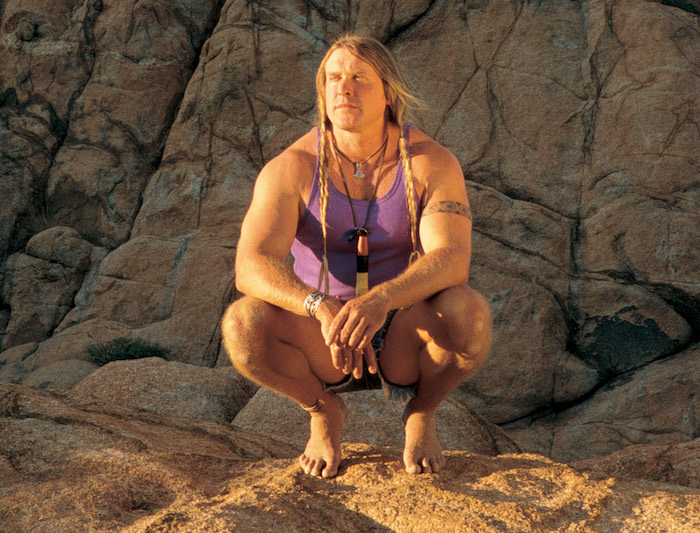

So we asked desert survival expert, author, and TV host Cody Lundin for his analysis. Since 1991, Cody’s operated the Aboriginal Living Skills School in Prescott, Arizona. He’s also known as the positive attitude “party on” host from Discovery’s Dual Survival.

Turns out that Cody and co-host Dave Canterbury were put in the near exact same scenario in the season 1, episode 4 episode “Desert Breakdown,” in which the pair were stranded in Peru’s Valley of the Volcanoes.

More: Take the best water survival course on the web so you’ll know exactly what to do in situations like this. Or find local teachers like Cody for in-person classes.

“It is foolish to travel into the desert, especially one named ‘Death Valley’ without more than adequate water. Trying to play the host on a phony TV survival show by using exotic methods of water procurement, while failing to prepare and bring water, risks death.”

The show might have been fake, but something Cody said in that episode is sadly all too true: “People die in the desert all the time. It’s not the real big thing that will take you out, it’s the little teeny things like we forgot the water or we took the wrong turn, the spare tire is flat.”

As always, we’re not trying to criticize the victims (in fact, there’s a bit to praise them for) and we/Cody don’t know enough of the situational details to draw exhaustive conclusions. But there are some key lessons here.

You can contribute to a GoFundMe for Lofgren and Henkel.

Important bits:

- Tell someone your plans before going on adventures. Without this step, Henkel might be dead.

- Prepare ahead of time by taking more water than you think you’ll need, a map, vehicle repair gear, etc. Any of those three things might’ve saved Lofgren.

- Stay put unless there’s a compelling reason to leave. Lofgren would likely be alive if they had stayed with their car.

- If you do leave, try to stay along developed paths and pick the destination that gives you the best chances of surviving. Lofgren might still be alive if they walked back the way they came instead of forging a new route.

- Use whatever resources you have, in this case pulling parts from the car. Breaking off and carrying a side mirror, for example, could’ve made a huge difference.

- Communicate however you can. The note they left on their abandoned car likely saved Henkel’s life.

What we know

Details are scarce, but based on these Arizona Central, WaPo, and CNN articles:

- Lofgren and Henkel were described as “experienced campers” who often spent time in remote areas.

- They left a backcountry itinerary ahead of time, specifying the places they were trying to visit and when they would return (April 4th).

- When they didn’t return, a missing persons report was made on April 6th.

- Search and Rescue started on April 7th.

- Rescuers first looked around common places like nearby hotels and the points from the backcountry plan, but found nothing.

- Air recon eventually found their abandoned car on April 8th near Gold Valley Road, an isolated location not on the original plan.

- The car had two flat tires. Given the rest of the details, we assume that means they didn’t have the ability to fix the problem.

- A note was left with the abandoned car: “Two flat tires, headed to Mormon Point, have three days’ worth of water.”

- Within an hour of finding the note, air recon found them trapped in steep Willow Creek Canyon in between the vehicle and Mormon Point.

- Air rescue tried to lower a hoist to lift up the couple, but the terrain made it too risky.

- So they had to bring in a ground-based team, who eventually reached the couple on April 9th — 5 days after their intended return and 2-3 days after SAR started.

Here’s a full 3D map of the area in Google Earth.

Lessons

Telling loved ones about their plans and their planned return date led to the relatively fast missing persons report when they were 1-2 days late.

In 98.6 Degrees: The Art of Keeping Your Ass Alive, Lundin recommends leaving a 5-W game plan with at least two trusted people, even for the simplest outdoor excursions:

- Where you will be going, with a 7.5-minute topographic map with destinations and routes clearly marked, as well as how long you intend to stay at each location

- When you will return

- What vehicle you’ll be driving, including make, model, color, license plate number, and other distinguishing characteristics

- Who is in your party, including names, sexes, ages, and medical conditions

- Why you’re taking the trip. Are you hiking, caving, canoeing, biking, hunting, etc.? Your reasons for taking the trip can clue rescuers in on your possible behaviors.

Unfortunately, they did not stick to the game plan they left ahead of time. “These people were in an area that was not on their itinerary, which in this case was a fatal mistake, and this is why SAR took several days to find their car, and then the people,” Lundin said. So even though a search and rescue was triggered when they didn’t return on time, their rescue was delayed because SAR didn’t know where to look. That was exacerbated by the couple’s lack of communications. There is little to no cellular service in Death Valley, and authorities were unsuccessful in trying to call their cell phones.

We later learn that they had three days worth of water for two people. That’s probably more than an average person would’ve brought on this trip, so these experienced campers deserve credit for not being stuck with just a single disposable bottle. Take more water than you need!

We have no idea about the condition of their Subaru before the trip, but if you’re going to go on adventures like this, basic maintenance is even more important so you minimize the chance of something irreparable breaking down.

It’s rarely practical to carry two spare tires. But a small tire repair kit might’ve been enough to plug/patch one or both of the tires. It’s unlikely that both tires blew out from being old — it’s more likely they hit something sharp on the road, and those kinds of rock/nail/etc punctures can be fixed with those tire repair products.

No communication method meant they were on their own. The official safety tips for Death Valley warn people not to depend on cell phones. And even though ham radio is excellent for preparedness/survival, there are recent reports indicating that Death Valley is a dead zone for VHF, which is what most handheld radios use.

So the best communication product to have on hand would’ve been a satellite communicator like a Garmin inReach that lets you send text messages and send out SOS beacons. They cost several hundred dollars and require a subscription, but in this case it would be worth every penny. You don’t even have to buy one: you can rent one from LowerGear Outdoors in Tempe, Arizona, near Death Valley, for $99 per week. Cheap insurance, and they ship to homes in Tuscon.

At minimum, a signal mirror can help you send SOS beacons up to 30 miles away. Cars also have mirrors, so Lofgren and Henkel could’ve removed any of the Subaru’s mirrors — that could’ve made a huge difference when signaling across the desert for help, and is something Cody and Dave did in their similar Dual Survival episode.

Although it likely wouldn’t have helped in this case (due to no cell signal), it’s worth noting that any form of communication can be helpful. Benjamin Kuo, call sign AI6YR, recently helped rescue a lost hiker thanks to a picture of the hiker’s feet that he sent to a friend just before his phone died. Kuo matched the photograph to satellite imagery and gave the location to rescuers. The hiker lived.

Deciding whether to stay with the car or walk out was likely the hardest decision of their experience. When making that decision, some of the key stuff to think about was:

- They knew they left an itinerary, so someone would know they were missing and come looking within days.

- They probably knew that they were stuck in a location not on their itinerary. So this becomes a judgment call of “how likely are they to find us?”

- They knew they had three days of water on hand, which means they could survive for 3-5 days. That’s probably enough time to cover both options of staying or leaving.

- It sounds like they had some rough idea of where they were and where they could walk to — either 22 miles back the way they came to a paved road or over wild terrain to another well-traveled road at Mormon Point, likely Badwater Road.

“Search and Rescue usually find the car first, and the dead body second. Vehicles are larger and therefore easier to find, like happened in this case,” Lundin said. Cars can also be reflective, which can help SAR spot them.

However, there are times when you may not have a choice but to leave the car, depending on multiple variables. “Like the wilderness itself, the decisions made are shades of grey, and are rarely black and white,” he said.

So in hindsight, it was probably the wrong decision to leave the car:

- The car is a pre-made, secure, waterproof shelter in an area without many alternatives.

- Assuming the only problem was flat tires, that means they could’ve turned on the car to signal (honk, flash lights, etc.) or use the AC/heater once in a while.

- The car was on/near a road. Although it’s not a popular road, it’s still a named route that people take in a popular national park, so there’s a chance someone would come by.

- SAR is also more likely to start searching along roads rather than random offroad areas.

It was probably also the wrong decision to walk offroad towards Mormon Point instead of walking back along the road they came. The decision is made to leave, now the choice is where to go. Between those two main options:

- It’s usually better to walk along developed roads/paths rather than going into the wild because you’re more likely to be seen. Lundin adds: “In general, you are easier to spot on a road, especially when you know someone will be looking for you, as they did leave a loose itinerary. SAR crews will first take the path of least resistance, roads and trails, etc. while looking for the lost.”

- Traveling on developed routes also means you’re less likely to get lost or hurt yourself.

- By going back the way they came, they at least know what to expect. All else being equal, you’d rather be in a situation with more intel than less.

- Distance doesn’t seem to be a deciding factor. Walking 22 miles back the way they came in that terrain for two young and (presumably) healthy people would take about a day. It doesn’t seem like the Mormon Point path was much shorter.

- The path they chose went through (what seems like) much rougher terrain. 5 miles over rough desert terrain might be a bad choice compared to 20 miles over easy terrain.

We hear this from survival experts all the time: Most people don’t think about what things will be like in between points A and B, they just think about the start, end, and a straight easy path connecting them — what’s in between matters!

We don’t know if the couple had a map. Given his experience and decision to walk to Mormon Point, it seems like he at least knew the area. In any case, a topographical map would be a big help when making the destination decision so you can see what’s in between. And “death by GPS” is a relatively common thing in these areas.

More: How to use a map and compass

So while there must’ve been some kind of justification to take the path they did, it proved to be the fatal flaw: Not only did they get stuck, but Henkel got hurt and Lofgren died when trying to cross a steep canyon area.

Leaving a note with the car was a great decision, especially since they specified where they were going and what critical resources they had (“3 days of water”). Although it took SAR a while to find the car, the note meant they found them within an hour.

There aren’t many details past that, so we can’t analyze things such as if they made smart decisions about water and shelter, if there’s something either of them could’ve done to keep Lofgren alive, etc.

You are reporting the comment """ by on